An interview with Mike discussing Mailer’s Last Days is featured on the January 31, 2023 episode of Deep Cover with host Damen Dynan. Listen on Apple Music.

Published in time for Mailer’s birthday, Ronald Fried has interviewed J. Michael Lennon about his latest memoir Mailer’s Last Days: New and Selected Remembrances of a Life in Literature, Lennon’s relationship with Mailer, and American literature in general. Fried writes:

At the age of 80, Lennon has lived long enough to see how writers’ reputations change over the decades. Since his death in 2007, Mailer’s reputation is still undergoing a transformation. To writers of my generation, Mailer was like a member of the family, in the good and the bad sense: omnipresent, sometimes disappointing, sometimes appalling, often brilliant, always calling attention to himself, and impossible to ignore. But to many younger literary types, Mailer is close to anathema, for his trafficking in misogynistic and racial stereotypes and the near-fatal stabbing of his wife Adele Morales, among other reasons. I talked with Lennon about his relationship with Mailer, Mailer’s contemporaries, and the challenges he faced as an academic and critic writing a highly personal memoir.

A review of Mailer’s Last Days by Robert Begiebing.

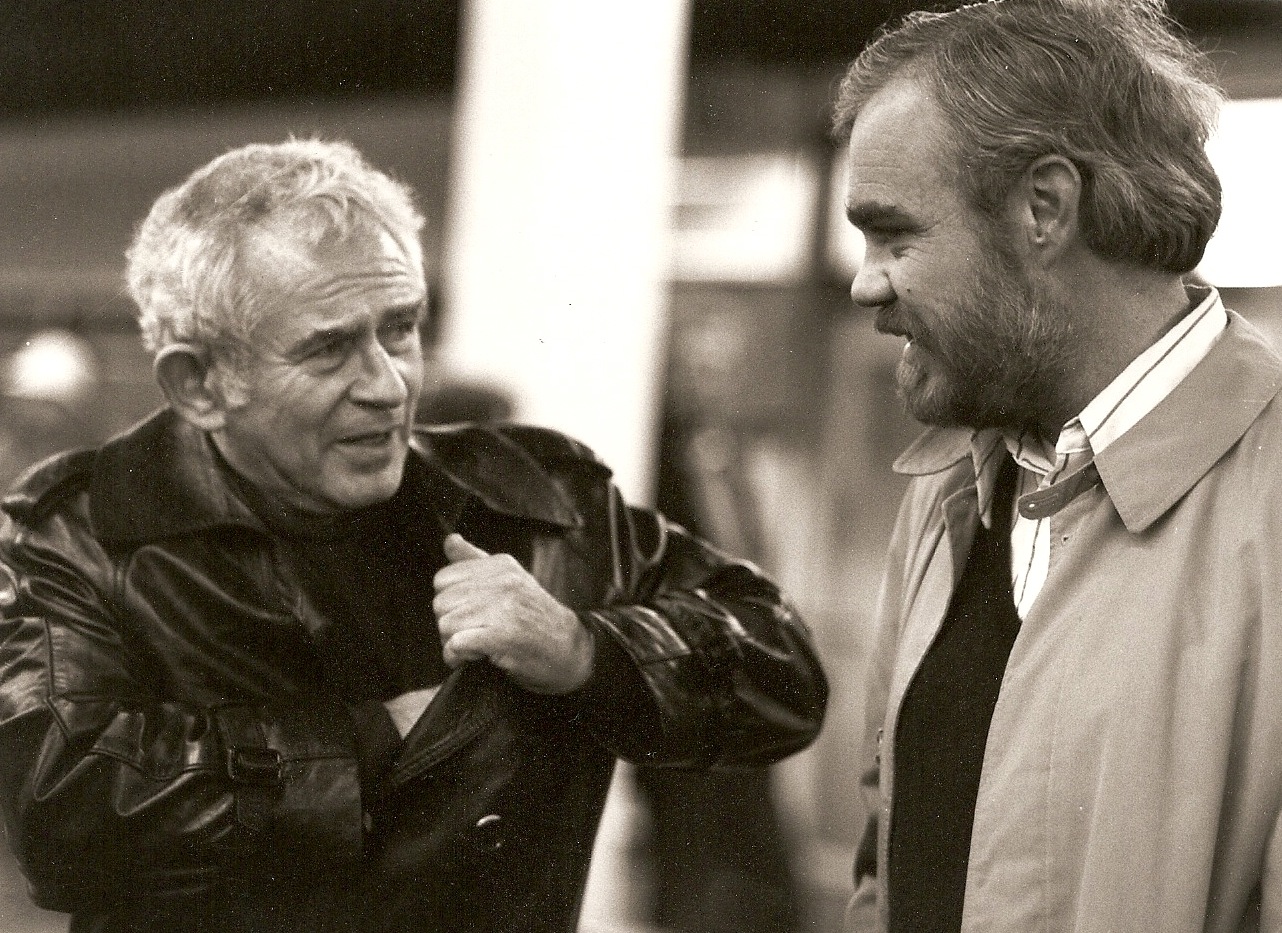

The title essay of J. Michael Lennon’s new book is a diaristic recounting of Mailer’s final illnesses, beginning in 2005, until his death in 2007, written by the man who eventually became Mailer’s closest literary colleague and confidante. How Lennon became close to Mailer is one tensile truss that binds the book and raises it beyond mere gallimaufry. The book is an artful amalgam of personal memoirs, critical essays on Mailer and his literary contemporaries, and interviews with and about Mailer.

Carl Rollyson writes: “Lennon knew Mailer for decades, interviewed him relentlessly, appeared in Mailer productions, edited and archived him, wrote his biography, and is probably as close to a modern Eckermann as we can get.”

Read the full review of Mailer’s Last Days in The Sun (subscription required).

Interviewed by Vicki Mayk

J. Michael Lennon’s literary identity has been intertwined with that of legendary writer Norman Mailer for more than a half century. As the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer’s authorized biographer and archivist, Lennon has written more about Mailer than anyone. The author of the biography Norman Mailer: A Double Life, published by Simon & Schuster in 2013, Lennon’s writing also has included essays, interviews, and literary criticism about many of Mailer’s contemporaries. In his new book, Mailer’s Last Days: New and Selected Remembrances of a Literary Life,Lennon makes his first foray into memoir.

Lennon is no stranger to the genre: As the co-founder of the Maslow Family Graduate Creative Writing Program at Wilkes University, where he is professor emeritus of English, Lennon has mentored many students writing memoir for their creative thesis. His new book marks the first time he has written his own memoir, tackling a braided form that includes examining the two fathers in his life – his biological father and Norman Mailer, who became another father figure during their long relationship.

Lennon (Norman Mailer: Works and Days), Norman Mailer’s archivist and biographer, gathers his own criticism, reviews, and personal essays in this varied collection. “The Archivist’s Apprentice” traces Lennon’s fascination with Mailer back to Lennon’s time in graduate school, when he proposed a doctoral thesis on Mailer, a proposition seen as questionable at the time because Mailer was still alive, and recounts Lennon’s time as Mailer’s archivist’s apprentice in the late 1970s. In the standout “Meeting Mailer,” Lennon recalls writing a fan letter to Mailer that led to a lifelong friendship, during which Lennon’s son thought Mailer “seemed more like a friendly uncle than a famous person.” Lennon also includes a grab bag of his reviews, among them of Don DeLillo’s Zero K (a “milestone”), Mary McCarthy’s Memories of a Catholic Girlhood (notable for the book’s “moving depiction of the gaping holes in family life”), and Joan Didion’s South and West (a collection that’s more than just a postmortem push for monetization, Lennon contends). These don’t have quite the same force that Lennon’s personal writing on Mailer does; here, the notoriously pugnacious Mailer comes off as a surprisingly approachable figure. Though it’s not all hits, this one’s worth it for the intimate literary insight. (Nov.)

From Publisher’s Weekly.

The Times Literary Supplement has published an excerpt from Norman Mailer’s Lipton’s Journal, edited by J. Michael Lennon, Gerald R. Lucas, and Susan Mailer: “Saint and Psychopath.” The entirety of Lipton’s will be published by what would have been Norman Mailer’s 100th birthday on January 31, 2023.

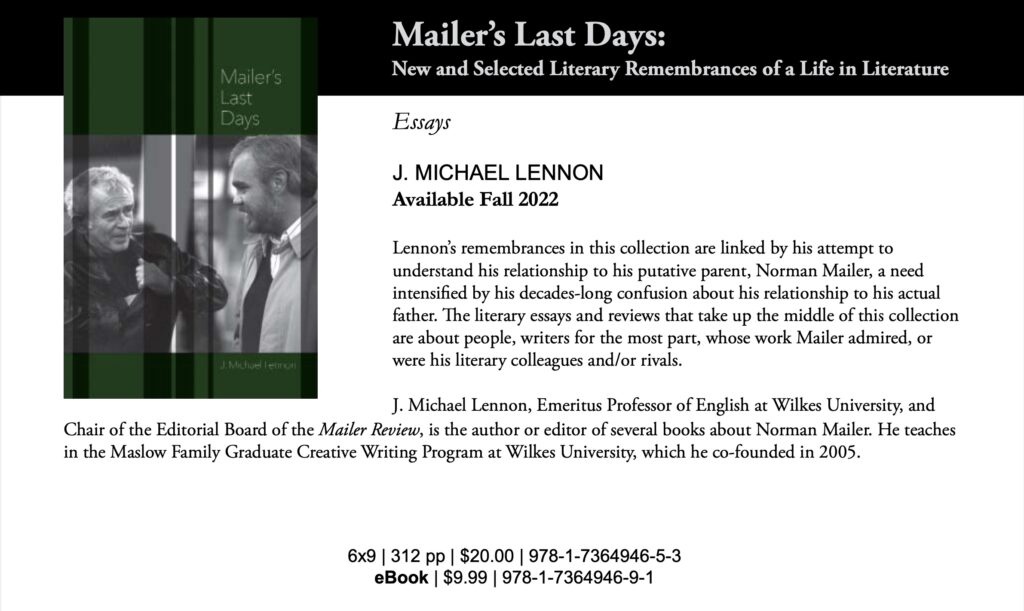

Coming Soon from Etruscan Press.

When I was a young professor at the University of Illinois-Springfield back in the 70s, I felt the same ardent longing described by Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, namely, the desire to have intense, candid, one-on-one conversations with the authors of books that knocked me out. I harbored this feeling in regard to two writers in particular: Joan Didion and Norman Mailer. In 1968, they each published a book that would thereafter be seen as their signature work, Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem, a collection of essays on the “atomization” of contemporary life, of things falling apart, set largely in California and other warm climes (her writer husband, John Gregory Dunne, once observed that “Joan never writes about a place that isn’t hot”), and Mailer’s The Armies of the Night, an arresting account of his participation in the tumultuous anti-war protests in Washington, D.C. in fall 1967, told oddly, but unforgettably in the third person, as if “Norman Mailer,” the protestor arrested for crossing a picket line at the Pentagon, was a character in a novel. In the romantic American line, Didion and Mailer deployed aspects of their prickly and passionate personalities in these books as prisms to portray a nation in turmoil, while also challenging long-established, respected, (if somewhat stale) modes of “objective” writing. Both books implicitly made the claim that the character and involvement of the writer was an indispensable element in how events were depicted, characters revealed, stories told. Like two earlier romantics, Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, Didion and Mailer were polar opposites: she, restrained, reclusive and sardonic and possessed of a icepick rhetoric that recalls Emily’s poems; he, brash, self-involved and as fond of his long-winded operatic voice as was Walt. Both were profoundly influenced by Hemingway, and shared an appetite for characters who believed that “salvation lay in doomed and extreme commitments,” as Didion once put it.

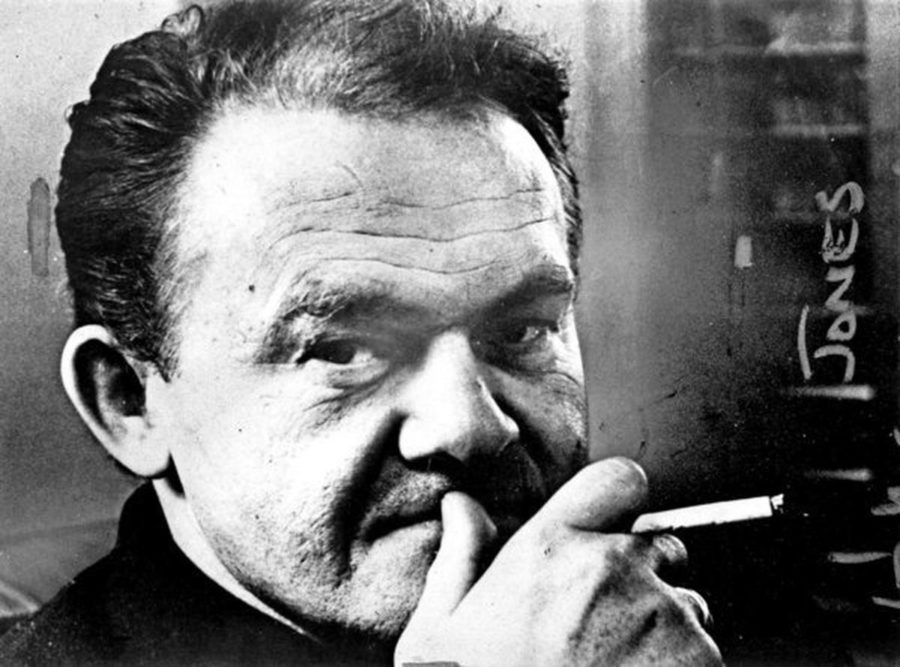

This month marks the 100th birthday of one of the most brilliant American writers of the mid-20th century, novelist James Jones, who died in 1977. Author of eight novels, a collection of short stories and several works of nonfiction, he is best remembered for his WWII trilogy, From Here to Eternity (1951), The Thin Red Line (1962), and Whistle (1978). Eternity won the National Book Award in 1952,and was made into a memorable film that won eight Oscars. But his 1958 novel, Some Came Running, a 1266-page portrait of postwar America (1946-49) moving into corrupt commercial overdrive, stands near the trilogy in imaginative scope and insight into the American condition. Jones always referred to it as his greatest achievement. His nonfiction work, WWII (1975), in which he analyzes the war from an enlisted man’s point of view, is also one of his enduring works. Upper class historians, Jones wrote from a viewpoint of idealism and economic security. The results are distorted, “and this is not to say the ideals are not eminently admirable. But they had almost no effect on your proletarian infantry soldier.” Jones was a grunt soldier. He was wounded at Guadalcanal, and received a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star.