Review of Avid Reader: A Life by Robert Gottlieb. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Times Literary Supplement (January 20, 2017)

Robert Gottlieb, the esteemed former editor-in-chief at two major American publishing houses, Simon and Schuster and Alfred A. Knopf, from the mid-1960s through the late 1980s, and editor of The New Yorker, from 1997-1982, has counseled, coddled, and hectored more important American writers (and some British) than anyone since Maxwell Perkins dealt with the distinctions and deficiencies in the prose and egos of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, James Jones, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe. A partial list of Gottlieb’s writers includes the following novelists: Sybille Bedford, Ray Bradbury, Anthony Burgess, John Cheever, Michael Crichton, Don DeLillo, Margaret Drabble, Joseph Heller, John le Carré, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, V.S. Naipaul, Edna O’Brien and Salman Rushdie. His nonfiction author list is just as stunning: Lauren Bacall, Bruno Bettelheim, Robert Caro, Bill Clinton, Nora Ephron, Antonia Frazer, Katharine Graham, Katharine Hepburn, Robert K. Massie, Jessica Mitford, William Shirer, and Barbara Tuchman. Plus a few musicians: Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Paul Simon. His writers have won all the awards—Man Booker, National Book Award, Pulitzer and Nobel. Now back at Knopf, Gottlieb, 85, and still going strong, is working with Toni Morrison, and awaiting the manuscript of the fifth and final volume of Caro’s biography of Lyndon B. Johnson.

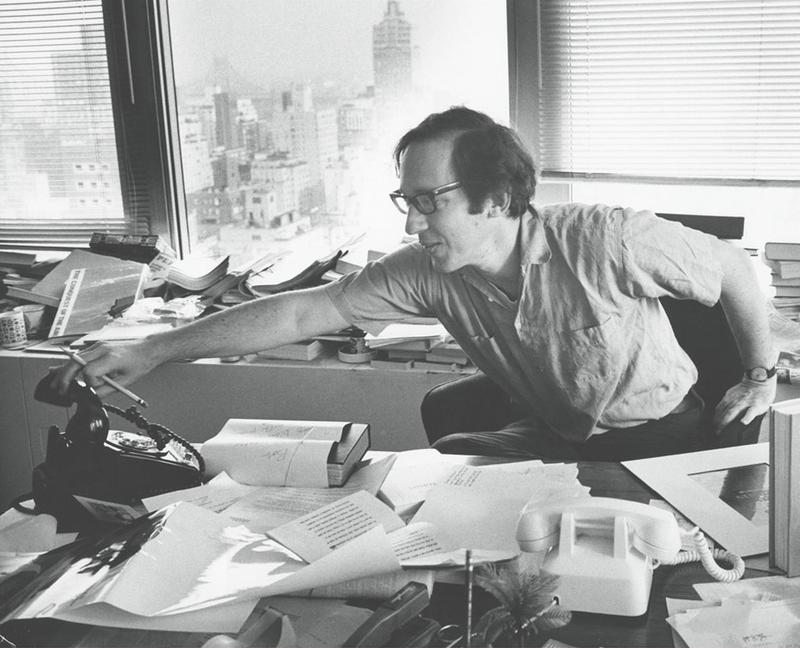

Given his fruitful involvement with all this talent, it is not surprising that Gottlieb was regularly encouraged by his friends to write about his professional life. He resisted. Why? In a Paris Review interview (fall 1994), he explains: “I dislike writing: it’s very, very hard,” he said, “I’m a talking animal, not a typing one.” Eventually, he caved in, but he could not entirely overcome his deep-seated aversion, and his memoir carries the hallmarks of hasty composition or cursory editing, or both. As le Carré put it, “Bob is voluble, speaks wonderfully and writes boringly. . . . He is all creative impulse and no creativity.” Avid Reader: A Life is full of stale phrases, sketchy anecdotes, and perfunctory accolades for all the wonderful guys and gals he’s worked with over the years. Too many paragraphs begin with “And then came…” or other lazy transitions. For long stretches, his memoir is a dog-trot along the washboard road of lit biz: blurbs, reviews, sales figures (Calories Don’t Count sold two million), jacket designs, print runs, and display ads (“our ads, everyone acknowledged, were the best in the business”). As I read, I kept muttering, “Editor, edit thyself!”

But his book, in compensation, is studded with a score of clear, sprightly accounts of how he solved thorny structural, stylistic, and personal problems over a half-century of interaction with his golden horde of idiosyncratic scribblers. Gottlieb was open to every solution, and had a different one for every writer. Some authors moved in with him and his wife, actress Maria Tucci, Anthony Burgess for one. He drank martinis with others, and ate tuna fish sandwiches while sitting on the floor of his office with still others (le Carré tired of these meals and had a clause added to his contract calling for Gottlieb to take him to a fancy restaurant). Unlike most editors, he reads first drafts in days, sometimes overnight, an ability that has endeared him to his writers, most of whom waited “in a state of suspended emotional and psychic animation.” Then comes a quick, honest estimate, and later, if necessary, a line-edit of the manuscript. “I have fixed more bad sentences,” he says, “than most people have read in their lives.” His mantra: “Do it now. Get it done. Check, check, and check again.” Widely read in virtually every prose genre, Gottlieb has a terrific eye for structure. He agreed to take on Chaim Potok’s The Chosen (1967) only if the author went along with his conclusion that the novel reached its natural conclusion halfway through the manuscript. Potok readily acquiesced and the division was made. He also accepted the title, one suggested to Gottlieb by a friend he bumped into going to the men’s room. The Chosen was both a critical success and a number one best seller.

Not all editorial fixes were this easy. Lauren Bacall was smart, and had “an enviable fluency as a writer,” but was insecure about her abilities as an actor, and had no idea what kind of a routine was needed to create her memoir. Gottlieb arranged for her to have an office at Knopf, and she came in daily, “working in longhand on long yellow legal pads, wandering around the office in her stockinged feet, getting coffee for herself, and chatting with the gang.” Every night the office staff would type up the day’s output for Gottlieb to read the next day. Their only disagreement came when Bacall saw the jacket design. The front cover of her memoir, By Myself, carried two striking photos of Bacall, and the back had one of her and her first husband, Humphrey Bogart.

Absolutely not, she exploded; this was her book, not his. That really pushed my buttons. “Listen, Bacall,” I said, “people want to know about you and him, and you’ve written hundreds of pages about him. It’s my job to sell your book, he’s the major selling point, and he’s going on the back cover.” “Fine,” she said. Like most actors, she responded positively to a strong directorial hand.

One of his happiest collaborations has been with Toni Morrison, who he convinced to quit her day job as a Random House editor, and devote full time to writing. After Knopf published her second novel, Sula (1973), which Gottlieb likens to a sonnet—“it’s contained, it’s precise, it’s utterly controlled”—he told her she should open up and attempt something more ambitious. Song of Solomon (1977) was her response. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and was cited in her 1993 Nobel citation. Morrison is almost exactly Gottlieb’s age and like him possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of the novelistic tradition. More important, he says, “we read the same way, so that when I make a suggestion, she instantly knows why, whether it’s about a sentence or involves a major structural issue.” When he suggested that the final third of one of her novels needed to be bulked up, “she saw why and solved the problem swiftly, perfectly, and untemperamentally.” Their concord is not entirely perfect, however:

Our only real disagreements have to do with commas, since she hates them and I love them. I put them in, she takes them out, and we trade. My guess is she doesn’t feel the need for them as strongly as I do because she’s hearing the text in her head supplying the punctuation, whereas I’m reading it, without benefit of her beguiling voice.

At the same time that Gottlieb was working on Sula, he was also immersed in one of his most challenging, and immense projects, The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s 1974 biography of the “master builder” of New York City, Robert Moses. Caro, an obsessive craftsman, spent years researching his subject, and when finished the manuscript was over a million words, which was 300,000 more than the binding technology of that era could accommodate. Caro agonized over every redaction and for a year he and Gottlieb “battled—hour after hour—over language, punctuation, repetition.” Caro leaned toward over-explaining, while Gottlieb was concerned that readers would be irritated by redundancy (he has kept a paperweight on his desk for sixty years that reads, “Give the reader a break”). So they fought and occasionally stomped out of the room when an argument grew too heated. Gottlieb, never one to waste time, used the cooling-off periods to visit other editors and get a little work done. Caro had nowhere to fume but the bathroom. The editing process took a year of focused effort. Gottlieb notes that the big haircut he gave the book was not just “a matter of snipping here and snipping there—you have to grasp a book as a whole in order to judge what there’s too much of (and also what there’s too little of).” The best editors are able to move with celerity and assurance back and forth from micro to macro, and everything in between.

Unless you are a fanatical fan of ballet (and even then), you might nod off reading Gottlieb’s chapter on how he managed two dance companies for a decade after being fired as editor of The New Yorker (owner S. I. Newhouse replaced him with Tina Brown). A devoted fan of ballet since his teenage years, Gottlieb recounts in hushed tones his sightings of George Balanchine, Lincoln Kirstein, Margot Fonteyn, and Mikhail Baryshnikov, and other New York City Ballet Company figures. When one of them, Natalia Makarova, comes to his home for dinner, she brings a box of Pampers for his two-year-old son, Nicky. This present, Gottlieb says, is a manifestation of Makarova’s “quintessentially Russian” temperament. Really. The key figure in the chapter is Lincoln Kirstein, the long-time General Director of the company, who Gottlieb says he learned more from than anyone he ever knew, but whatever it was remains a secret. He drones on about committee meetings, foundations, union negotiations (Kirstein loathed musicians is the takeaway). His account of managing the Miami Ballet Company is a notch more soporific, as he discusses the challenges of coordinating the artists, choreographer, ballet mistress and stage manager. He explains that Miami Ballet Company choreographer Twyla Tharp “works harder than just about anyone I’ve ever known.” They pig out together occasionally on Häagen-Dazs, he adds, omitting their preferred flavors. There are lots of little thankyous and kudos for friends and colleagues, including one for Esther Percal, “the queen of Miami Beach real estate” who, he says, has “a big personality, a big wardrobe, and an even bigger heart.” At this point, I threw the book across the room.

The Paris Review interview mentioned earlier, “Robert Gottlieb: The Art of Editing I,” contains some rich, revealing accounts of Gottlieb’s editorial finesse, along with quick portraits of the many great writers he has worked with over the decades. The amplifying responses of these writers—Lessing, le Carré, Morrison, Crichton, Caro, and few others—alternate with Gottlieb’s words. These interviews, interleaved with the best dozen accounts of his engagement with writers in Avid Reader, would make a nifty handbook of editorial technique. The best person to take on this job of work would be one of the finest editors in the profession, Robert Gottlieb, who sits at the feet of the editor he calls “the paragon of paragons,” Maxwell Perkins.