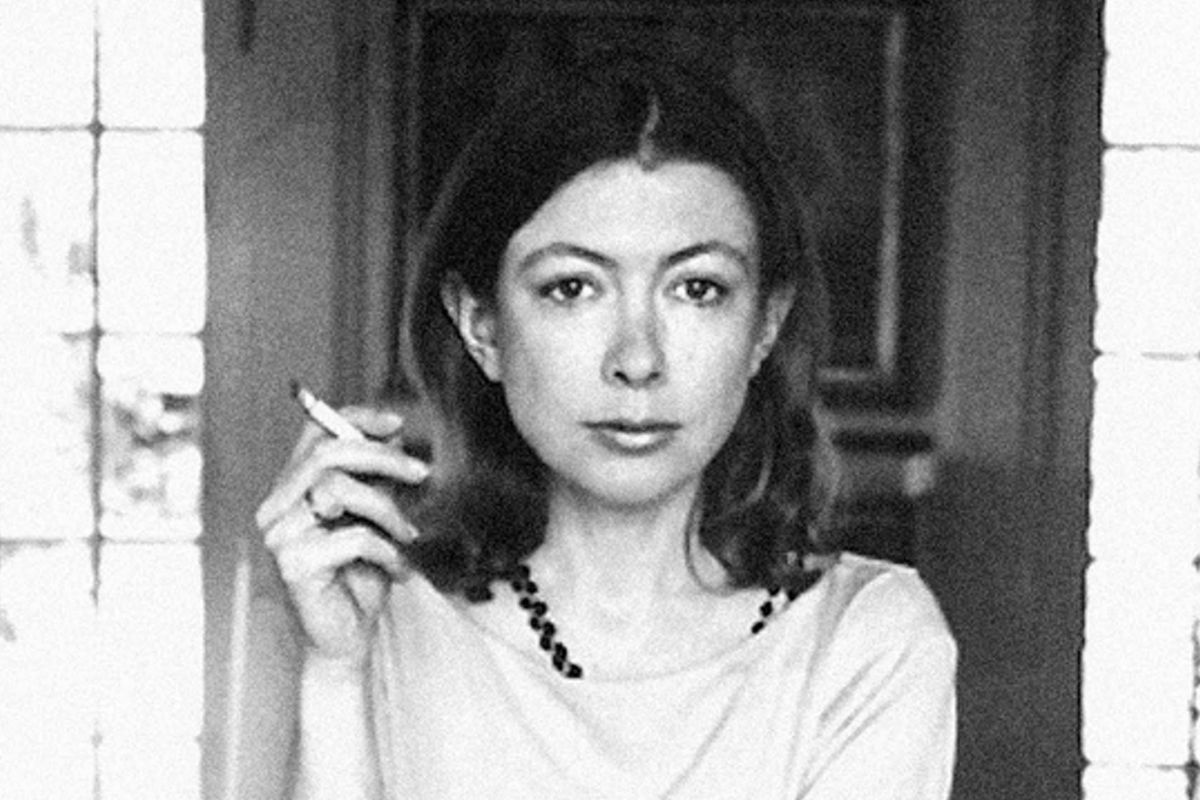

Joan Didion’s late husband, John Gregory Dunne, once pointed out that “Joan never writes about a place that isn’t hot.” During the late ’60s and ’70s, Didion lived in and wrote about climes of shimmering heat where apathy, violence and paranoia jostle, and snakes glide through the swimming pools.

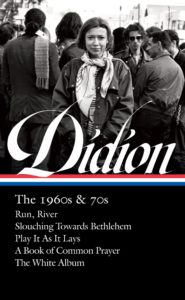

Draw a line from Hawaii that runs the length of California, jogs across the desert to Las Vegas, moves east-southeast to New Orleans and Miami, then due south to the countries near the equator and you will find the settings for Didion’s novels: “Run River,” “Play It as It Lays” and “A Book of Common Prayer” as well as the majority of the essays in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The White Album.” All of these works are gathered in “Joan Didion: The 1960s & 70s,” the first of several planned volumes of her work from the Library of America. (The only significant departure from these balmy settings is New York City, which Didion has written about occasionally, most notably in an evocative valedictory essay, “Goodbye to All That.”)

As in the work of Tennessee Williams, whose affection for sultry weather and nostalgia for a mythical past are mirrored in Didion’s work, sexual activity in these three novels is roughly congruent with the temperature of the locale, although less so in her emotionally persuasive first novel, “Run River.” The book, which takes place mainly in the ’50s in the Sacramento River Valley, is the portrait of an always-failing, never-dissolving adulterous marriage between the scions of two of the richest landowning families, Lily Knight and Everett McClellan. Despite mistakes and betrayals, Knight never relinquishes her desire to return to a stable past, “to that country in time where no one made a mistake,” the Edenic California celebrated by her (and Didion’s) parents.

The Old West of legend, now somewhat tarnished, is also present in Didion’s next novel, “Play It as It Lays.” The central character is Maria Wyeth, a minor film actress who grew up in and around Reno, Nev. She is raised by a gambler father who teaches her that the lessons of life are akin to the action at the craps table, and a mother whose corpse is eaten by coyotes after a desert car wreck. Drenched in dread, Wyeth’s story is told mainly by an anonymous narrator via 84 flashback scenes reamed with abrupt, enigmatic silences. The frame for the novel’s action depicts Wyeth confined in a psychiatric hospital watching a hummingbird outside her window, and recalling the debilitating events of her recent life — bad lovers, a semi-pornographic film, an abortion, her parents’ deaths, her director-husband’s desertion, and a daughter born with a neurological illness. Perhaps the most dazzling of these chapters is an early one that describes Wyeth taking day-long daily drives on the California freeway, an activity which is both an escape and a desperate attempt to exercise some control over a life in shambles.

Her third novel, “A Book of Common Prayer,” is the most complex and to my mind the least realized. In “The White Album,” Didion describes a time in the late ’60s when she was deeply distressed by the shocking events of that period — the assassinations, protests, riots, the Manson murders, and the rest. Her life at that time had lost its narrative line. “All I knew is what I saw,” she wrote. “Flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience.” This vision captures precisely the jagged, baffling flow of “A Book of Common Prayer.” The narrator, Didion’s version of Joseph Conrad’s Marlow in “Lord Jim,” is Grace Strasser-Mendana, an American who has married into the ruling family of Boca Grande, the country where the book is set. Sick with terminal cancer, she observes and tries to understand the purposes of another American, the psychologically damaged Charlotte Douglas, a 40-year old woman from San Francisco, who is murdered in one of the small-bore revolutions that periodically roll through this fictional equatorial nation.

In “The White Album,” Didion said that her highest admiration was for fictional characters who believe that “salvation lay in extreme and doomed commitments, promises made and somehow kept,” but Charlotte Douglas’s are a dark mystery. Her listlessness reinforced my conclusion that Didion will be best remembered for her autobiographical nonfiction where she crisply parses and delineates her feelings and observations. As she remarked in a 1979 interview, “If you want to write about yourself, you have to give them something.” The two essay collections in this volume and her 2005 memoir “The Year of Magical Thinking” (not included in this collection), are where Didion gives the most, putting herself, firmly but gracefully, on the stage of the story and delivering her finest character.