David Denby took on quite a job of work when he decided to depict the lives of four famous 20th-Century Americans: Leonard Bernstein, Mel Brooks, Betty Friedan, and Norman Mailer in Eminent Jews (Henry Holt and Co.; April 2025).

Tag: Norman Mailer Page 1 of 2

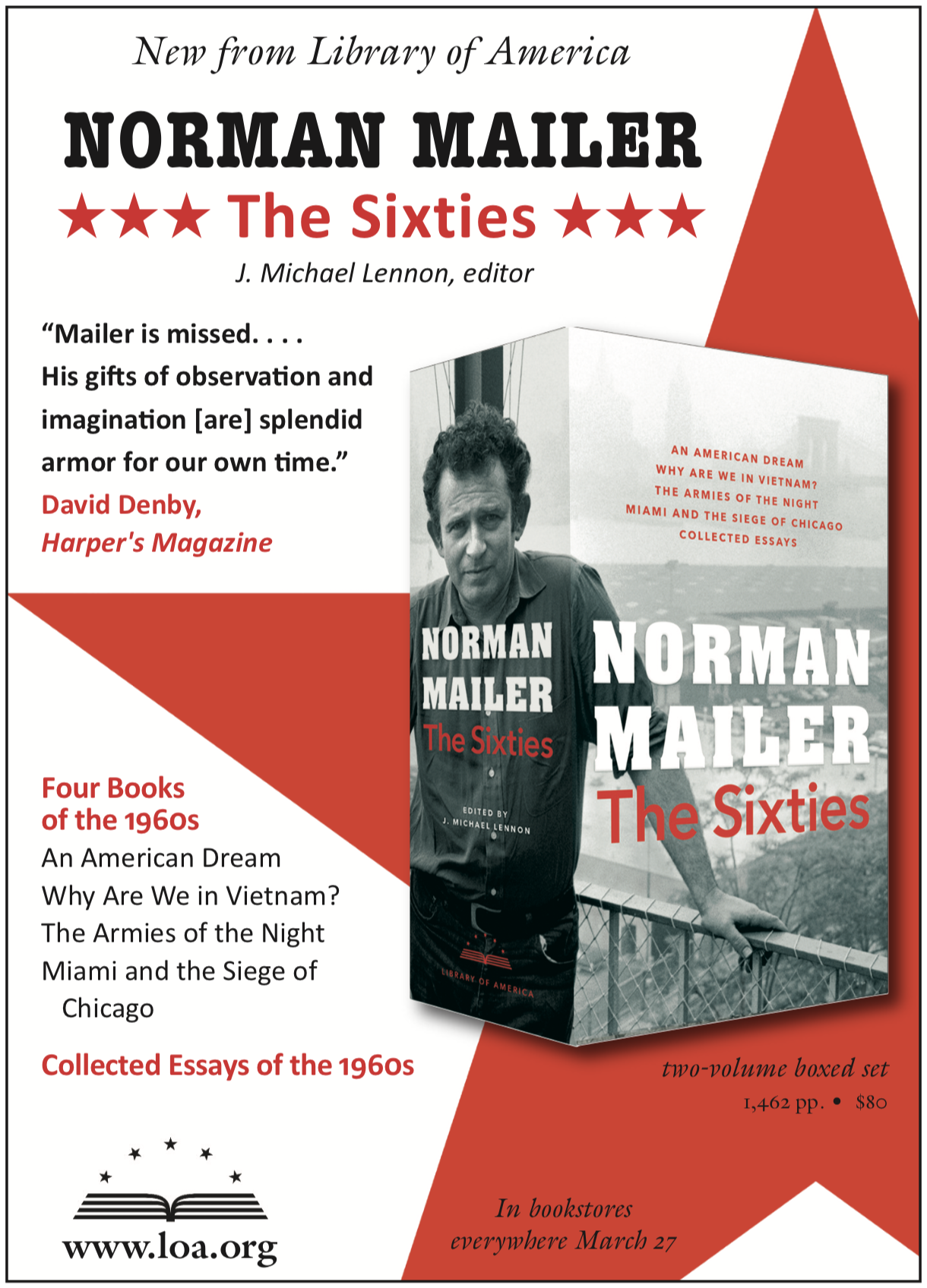

No writer plunged more wholeheartedly into the chaotic energies of the 1960s than Norman Mailer, as he fearlessly revolutionized literary norms and genres to capture the political, social, and sexual explosions of an unsettled era.

“No one in the literary world told us more about what was going on in the 1960s politically, socially, and sexually than Mailer.”

Purchase Norman Mailer: The Sixties: A Library of America Boxed Set on Amazon.

Mike says: The Times Literary Supplement (London) asked to post an excerpt from Norman Mailer’s last interview (September 2007) with yours truly to its website. The interview concerns the VILLAGE VOICE, which announced a few days ago that it was suspending print publication after 62 years. Mailer speaks of the newspaper’s origins—he helped fund it, and also came up with the name. Please pass on to interested people. The piece first appeared in The Mailer Review a couple of years ago.

DID YOU KNOW? The first preface, foreword or introduction to the work of another writer that Mailer wrote was for Seymour Krim’s 1961 collection of essays, Views of a Nearsighted Cannoneer (Excelsior Press). Krim, a Greenwich Village hipster who was sometimes described as a scaled-down version of Mailer, met Mailer in the early 1950s, and wrote several essays about him, including a wonderful, funny, tissue of complaints in New York (April 1969), “Norman Mailer, Get Out of My Head.” Along with Allen Ginsberg and Noel Parmental, Jr., Krim was supposed to be one of Mailer’s press secretaries in his aborted campaign for mayor of New York on the Existential Party ticket. Prior to writing the foreword for Krim’s collection, Mailer had been averse to writing such pieces on the grounds that he was diluting his own work. But as time went on, he wrote dozens of them for various friends. Here is the foreword, in its entirety:

Krim in his odd honest garish sober grim surface is a child of our time. I think sometimes, as a matter of style, he is the child of our time, he is New York in the middle of the 20th Century, a city man, his prose as brilliant upon occasion as the electronic beauty of our lights, his shifts and shatterings of mood as screeching and true as the grinding of wheels in a subway train. He has the guts of New York, old Krim, and it is not so impossible that when the digital computer in the mind of new historians begins to tick over the psychic ash heaps and spiritual dumps of this insane, cruel, rapacious, avid, cancerous and alas—in the end—cowardly city, they will say if they have a sense of the past that yes, in the work of Seymour Krim lives one of the truest beats of how horrible, how jarring, how livid and how exciting was this city where the best of us burned and burned without a war, an underground, or a passion for the blood.

Norman Mailer

New York, September 1960

Being a writer means being able to do the work on a bad day.

Norman Mailer

DID YOU KNOW? Mailer’s books were published by several American publishers, but the most important were Rinehart (1948-54), Putnam’s (1955-67); New American Library (1968-72), Little, Brown (1971-83), and Random House, from 1984 until his death in 2007. Random House published eight of his books, and will publish his selected essays in fall 2013, and his selected letters in fall 2014.

DID YOU KNOW? The last short story that Mailer wrote was “The Last Night,” published in the December 1963 Esquire. It is a sci-fi tale about the world ending after a devastating nuclear war. The president of the U. S. and the premier of the U. S. S. R. recognize that radioactive fallout has made the Earth almost inhabitable. They agree to a bold course of action: load the most advanced spaceship with 80 humans, all healthy and intelligent, representing the races and culture of the world, add some animals and computers containing some portion of the planet’s cultural heritage, and send it out into the universe. Because the best rockets of the time will be unable to propel the ship beyond the Earth’s gravitational pull, the leaders decide to explode the earth after the spaceship-ark has been launched in the hope that the massive detonation, which will destroy the planet, will propel the ship out into deepest space. The resident tells the premier that he believes that “man may have been mismated with earth,” and

We cannot suffer ourselves to sit here and be extinguished, not when the beauty that first gave speech to our tongues commands us to go out and find another world, another earth, where we may strive, where we may win, where we may find the right to live again.

In a plebiscite, the people of the earth vote favorably to destroy the planet. The story ends with “the spaceship, a silver minnow, streaming into the oceans of mystery, and the darkness beyond.” It was Mailer’s intention to use this ending as the hinge between the end of Ancient Evenings (some may recall that the novel ends with “the scream of the earth exploding”), and the unwritten sequel, “The Boat of Ra,” which would detail the spaceship’s voyage to distant galaxies. There is quite a bit more to the story, including the nature of the final novel of the trilogy, “Of Modern Times,” all detailed for the first time in Norman Mailer: A Double Life.