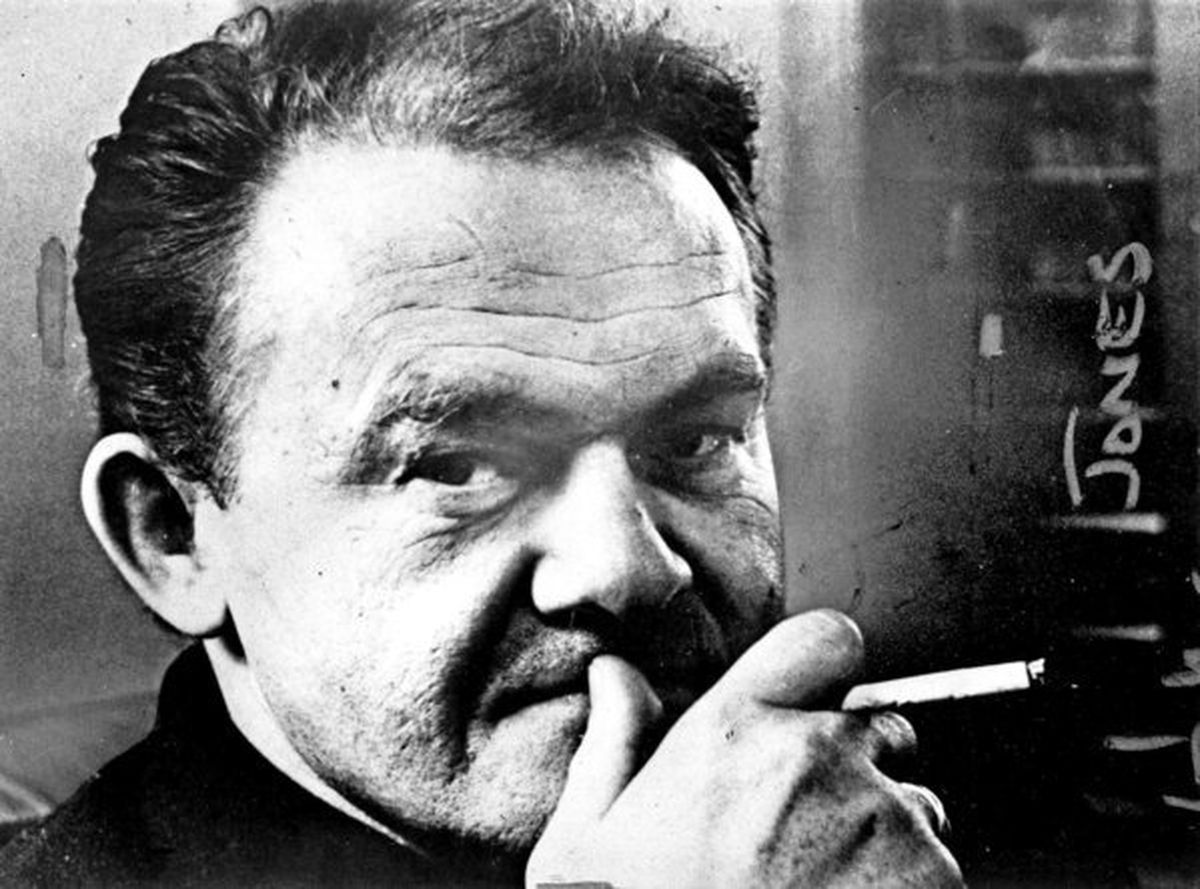

This month marks the 100th birthday of one of the most brilliant American writers of the mid-20th century, novelist James Jones, who died in 1977. Author of eight novels, a collection of short stories and several works of nonfiction, he is best remembered for his WWII trilogy, From Here to Eternity (1951), The Thin Red Line (1962), and Whistle (1978). Eternity won the National Book Award in 1952,and was made into a memorable film that won eight Oscars. But his 1958 novel, Some Came Running, a 1266-page portrait of postwar America (1946-49) moving into corrupt commercial overdrive, stands near the trilogy in imaginative scope and insight into the American condition. Jones always referred to it as his greatest achievement. His nonfiction work, WWII (1975), in which he analyzes the war from an enlisted man’s point of view, is also one of his enduring works. Upper class historians, Jones wrote from a viewpoint of idealism and economic security. The results are distorted, “and this is not to say the ideals are not eminently admirable. But they had almost no effect on your proletarian infantry soldier.” Jones was a grunt soldier. He was wounded at Guadalcanal, and received a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star.

Along with his friend and fellow infantryman, Norman Mailer, Jones is a tutelary spirit of the Maslow Graduate Creative Writing Program. His daughter, novelist and memoirist Kaylie Jones, is a founding faculty member, and her friend, Laurie Loewenstein, also a Program faculty member, is the current president of the James Jones Literary Society. Bonnie Culver and I have also served presidential terms. Each year since 1992, the Society has selected a winner of the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, which now comes with a $10,000 first prize (there are two additional prizes for runner up), and the majority of the winners have had their novels published. Jones always held out a helping hand to unsung writers, and the prize is an effort to continue his generosity. Kaylie has also been instrumental in the republication of her father’s works by Open Road Media, including an uncensored version of Eternity. She is also the author of a moving and evocative memoir, A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries (1990), which was later made into a Merchant-Ivory film.

I’ve also written about Jones, and I’ll close with a quotation from the introduction to a 1991 collection I edited with James R. Giles, The James Jones Reader:

The conclusion of Jones’s first published novel—the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—was the beginning of his combat experience. He was the only future novelist of note on active duty on December 7, 1941. But From Here to Eternity is not a combat novel. It is an army novel, perhaps the finest ever written by an American, and is in fact dedicated to the United States Army. Most of the novel’s action takes place at Schofield Barracks, where Jones served until shipping out in 1942 for Guadalcanal. Eternity is the first of trilogy of novels that follows an infantry company from the caste-ridden, authoritarian peacetime army through Pearl Harbor, ferocious combat in the South Pacific, and back to military hospitals in the United States. “Authenticity” is the word used over and over in reviews and essays on the novel. This is a tribute, in part, to Jones’s massive documentation of the gear, tackle, drills, bugle calls, boredom, KP, masochism and camaraderie—in short, all facets of barracks, bivouac, and stockade life in the “old” pre-war army. Although Eternity (860 pages) is clearly a novel of saturation in the Dreiserian tradition, it rarely flags. Its narrative drive and pace are tremendous. Jones writes with the classic realistic novelist’s confidence that the world can be understood and explained. His epigraph notes that “the whole of history is in one man.” Jones’s man is Pvt. Robert E. Lee, a romantic rebel he first described as “a small man standing at the edge of the ocean shaking a fist.” Jones was able to make so much out of Prewitt, Sgt. Warden, Pvt. Maggio and the other GIs and their life in D quad and the stone quarry and the bars and brothels of Honolulu because, as Joan Didion has pointed out, “James Jones had known a great simple truth: the Army was nothing less than life itself.”