As an editor-in-chief at two American publishing houses, Simon and Schuster and Alfred A. Knopf, from the mid-1960s through the late 80s, and as the Editor of the New Yorker from 1982–97, Robert Gottlieb has coddled and hectored more important American writers (and some British) than anyone since Maxwell Perkins dealt with the distinctions and deficiencies in the prose and egos of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, James Jones, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Thomas Wolfe.

WEST LONG BRANCH, N.J. – (Sept. 16, 2016) – The Norman Mailer Society, in partnership with Monmouth University’s Wayne D. McMurray School of Humanities and Social Sciences, will hold its 14th annual conference on campus from Sept. 29 to Oct. 1. Barbara Mailer Wasserman, Long Branch native and sister of the late Norman Mailer, will provide the keynote address, “Mailer Roots in Long Branch.” Also included in the conference will be a reading by Monmouth Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing Alex Gilvarry from his upcoming novel, Eastman Was Here and a performance of the one-woman play, A Ticket to the Circus, by Bonnie Culver, based on the memoir of Mailer’s wife, Norris Church Mailer, performed by K.C. Leiber.

Danielle Mailer enlisted local volunteers to help create a mural-like work, with enormous fish covered in bright patterns, along the Naugatuck.

Follow your passion, write your story, and work to get published with the Maslow Family Graduate Program in Creative Writing at Wilkes University.

Young in Springfield, Lincoln enjoyed a deep relationship with Joshua Speed.

In 1834, Joshua Speed, an ambitious young man from a well-to-do Kentucky family, set up a dry goods store in a two-story brick house on the corner of Fifth and Washington Streets in Springfield. Located on the town square in the commercial and governmental heart of what would become the state capital five years later, Speed’s store thrived financially. By 1839, it was also a gathering place for the male “lights” of the community, men who sought a congenial spot for coffee and cider, professional exchanges and gossip, political discourse (sometimes sharp-edged), and storytelling (often comic). Stephen Douglas, later an Illinois senator, often joined the group, as did several prominent judges, businessmen, lawyers and legislators. But Abraham Lincoln, who had only recently been admitted to the bar, was the magnet, the charismatic speaker who drew the intellectuals and politicians to the regular evening meetings.

Zero K, DeLillo’s sixteenth novel, is a probing examination of the ethics and techniques of cryonics – that is, the freezing of dead people (at present, cryopreservation can only take place after “legal death”).

Saturday, April 23rd, from 10am to 3:30pm, at School One. $50 for one, or two tickets for $80.

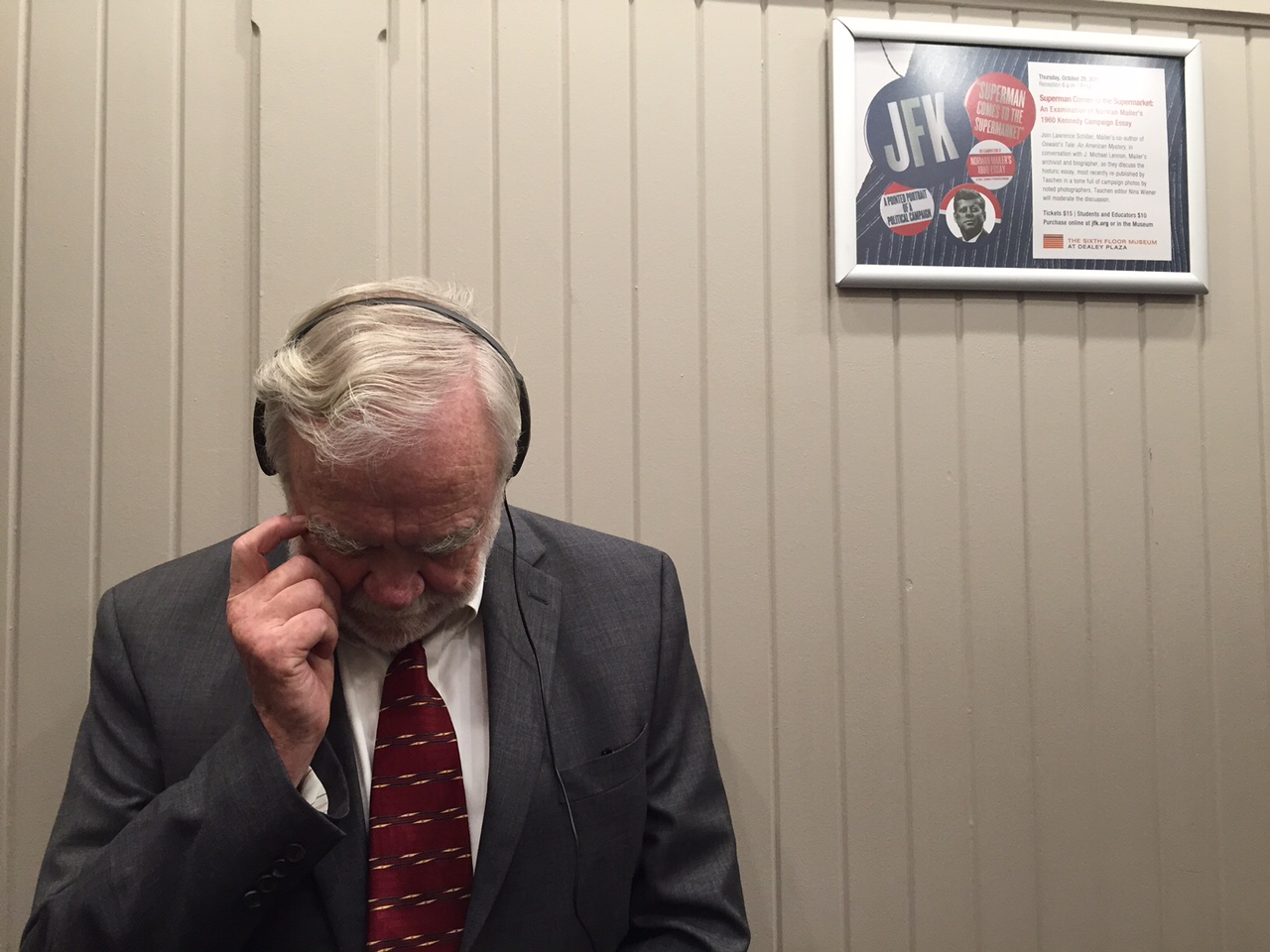

Before anyone foresaw a time when a television celebrity could become president, Norman Mailer wrote in Esquire that John F. Kennedy was a mythical hero who could finally unite the business of politics with the business of stardom. His legendary 1960 reported essay, “Superman Comes to the Supermart,” about J.F.K. and the Democratic political convention, changed the rules for how we understand our political candidates as brands, and how we’re allowed to write about them. Mailer archivist and biographer J. Michael Lennon joins host David Brancaccio to discuss Mailer’s legacy, what his essay wrought, and how it continues to ripple through our political culture and be proven prescient again and again.

Mike reviews Cannot Stay: Essays on Travel by Kevin Oderman.

Once you walk into the airport “you’ve already begun to be someone else,” writes Kevin Oderman in his collection of deeply felt meditations on the art of travel (Cannot Stay: Etruscan Press, 2015).

In prose that shows labor limae et mora, the long, slow work of paring and polishing, he registers the jolts and quivers to his consciousness arising from his brushes with the weird, the recondite, the revolting, and the sublime in his trips around the globe.