Mike and Barbara Wasserman. Photo by Donna Pedro Lennon.

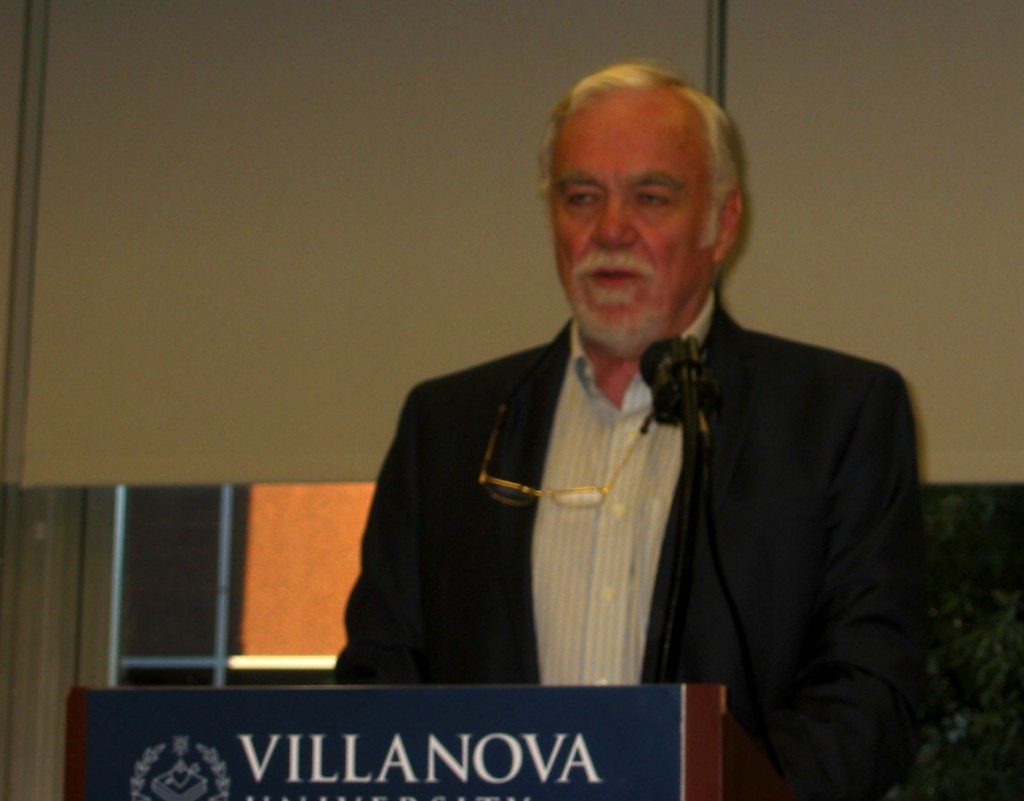

7 p.m., Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2013

Ballroom, Henry Student Center

Wilkes University, 84 W. South Street, Wilkes-Barre

Book signing immediately following. Reception for Dr. Lennon following the reading in Kirby Hall.

Please RSVP by Friday, Nov. 1, to confirm your attendance at the reception by calling or emailing Rebecca Van Jura at 570-408-4306 or email [email protected]

Parking available behind Henry Student Center

Published in Narrative 7 (Fall 1977), 170-88.

“What is life but the angle of vision? A man is measured by the angle at which he looks at objects.” Emerson, “Natural History of Intellect”

Norman Mailer’s development as a writer parallels at every point his growing awareness of the difficulty, and doubtful wisdom, of attempting to separate his personal and artistic worlds. His desire to build “the radical bridge from Marx to Freud,” to link public event and private sensibility, was not announced until 1958. Before that time, incredible as it may seem given his ubiquitous presence in our literary life over the past ten or fifteen years, Mailer attempted to segregate his personal and artistic worlds. . . .

After writing and then fighting for the publication of The Deer Park, Mailer reconsidered the experience in a long essay later published in his omnibus volume, Advertisements for Myself (1959). By now, his perspective had begun to shift. The fact that he referred to Advertisements as “this muted autobiography”, and explained that he had “decided to use my personality as the armature of this work,” shows just how much his conception of the relationship between the artist and his work had begun to change. From the time of Flaubert on, writers began to see themselves more and more as aesthetic artificers and less as purveyors of the egotistical sublime. The role of the novelist as detached craftsman was refined and transmitted to the twentieth century by Conrad and James, and then further exalted by Joyce. As a young writer Mailer accepted implicitly the tradition of the novelist as a detached creator whose method was “objective” or “dramatic,” as René Wellek and Austin Warren define it, rather than the opposed tradition that Wellek and Warren call the “romantic-ironic mode.” Mailer has more in common with Rousseau than Flaubert.

Mailer’s battle with the American publishing industry over the supposed obscenity of The Deer Park was the event that punctured what he calls his “nineteenth century naïveté” and made him “a psychic outlaw.” Mailer now raked through the “personal affectations and nervous susceptibilities” that Flaubert believed the artist should transcend. Essays like “The White Negro,” “The Last Draft of The Deer Park, the “Quickly” columns from the Village Voice, and most of the “Advertisements” that connected these and other short pieces in Advertisements were direct expressions of Mailer’s latest ideas and experience. He later defined experience as “the church of one’s acquired knowledge.”

Dear Friends,

Today I received the first copy of Norman Mailer: A Double Life, which gave me a clear and present thrill. The bio came in at 947 pages—763 of text, the rest are devoted to notes, bibliography, index, and acknowledgements. The photos, 53 of them, are clear and well-presented. Most of them have not been seen before.

It will be in bookstores on October 15, and I am told that reviews of it should begin appearing around that time. Amazon has just reduced the price of the book to $24; the e-book version is $19.99.

Simon & Schuster publicity chief, Maureen Cole, just sent me the attached information sheet on the bio, and a brief Q and A. If you would like to review the book, or have questions about readings and appearances, she can be contacted at maureen.cole@simonandschuster.

Thanks to all of you who helped me on this project over the past seven years, and earlier. There is always a posse of supporters riding with biographers to round up the information needed for their books, and I am fortunate to have so many thoughtful friends and colleagues helping out.

Gratefully,

Mike