When I was a young professor at the University of Illinois-Springfield back in the 70s, I felt the same ardent longing described by Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, namely, the desire to have intense, candid, one-on-one conversations with the authors of books that knocked me out. I harbored this feeling in regard to two writers in particular: Joan Didion and Norman Mailer. In 1968, they each published a book that would thereafter be seen as their signature work, Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem, a collection of essays on the “atomization” of contemporary life, of things falling apart, set largely in California and other warm climes (her writer husband, John Gregory Dunne, once observed that “Joan never writes about a place that isn’t hot”), and Mailer’s The Armies of the Night, an arresting account of his participation in the tumultuous anti-war protests in Washington, D.C. in fall 1967, told oddly, but unforgettably in the third person, as if “Norman Mailer,” the protestor arrested for crossing a picket line at the Pentagon, was a character in a novel. In the romantic American line, Didion and Mailer deployed aspects of their prickly and passionate personalities in these books as prisms to portray a nation in turmoil, while also challenging long-established, respected, (if somewhat stale) modes of “objective” writing. Both books implicitly made the claim that the character and involvement of the writer was an indispensable element in how events were depicted, characters revealed, stories told. Like two earlier romantics, Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, Didion and Mailer were polar opposites: she, restrained, reclusive and sardonic and possessed of a icepick rhetoric that recalls Emily’s poems; he, brash, self-involved and as fond of his long-winded operatic voice as was Walt. Both were profoundly influenced by Hemingway, and shared an appetite for characters who believed that “salvation lay in doomed and extreme commitments,” as Didion once put it.

Category: Misc Page 1 of 2

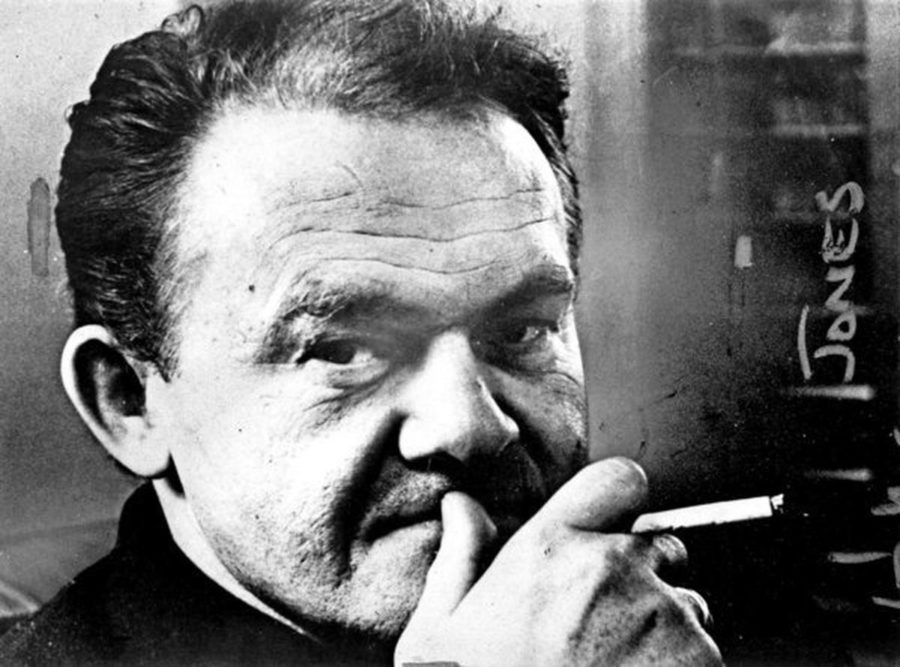

This month marks the 100th birthday of one of the most brilliant American writers of the mid-20th century, novelist James Jones, who died in 1977. Author of eight novels, a collection of short stories and several works of nonfiction, he is best remembered for his WWII trilogy, From Here to Eternity (1951), The Thin Red Line (1962), and Whistle (1978). Eternity won the National Book Award in 1952,and was made into a memorable film that won eight Oscars. But his 1958 novel, Some Came Running, a 1266-page portrait of postwar America (1946-49) moving into corrupt commercial overdrive, stands near the trilogy in imaginative scope and insight into the American condition. Jones always referred to it as his greatest achievement. His nonfiction work, WWII (1975), in which he analyzes the war from an enlisted man’s point of view, is also one of his enduring works. Upper class historians, Jones wrote from a viewpoint of idealism and economic security. The results are distorted, “and this is not to say the ideals are not eminently admirable. But they had almost no effect on your proletarian infantry soldier.” Jones was a grunt soldier. He was wounded at Guadalcanal, and received a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star.

In Growing Up on the Gridiron, Vicki Mayk tells the story of Owen Thomas, his family, teammates, friends, and coaches and explores the health concern he helped to illuminate. It’s also the story of Dr. Ann McKee, the Boston University-based neuropathologist who bucked conventional wisdom and the football establishment, as she studied Owen’s brain and its larger significance.

J. Michael Lennon: As a practicing psychoanalyst, you have published professional papers, but this is your first creative work. Why did you decide to write a memoir?

Susan Mailer: In 2013 I was invited to be the keynote speaker at the Norman Mailer Society Conference. I decided to write a personal vignette that would shed light on an unknown aspect of my father’s life. Immediately, I remembered those months Dad had spent in Mexico when I was a small child and had taken me to the bullfights. I hadn’t thought about the corridas in more than 40 years, but the images were all there, waiting to be retrieved: the music, the atmosphere, the smell of beer and Mexican snacks, people cheering, and most of all the black bull running, panting, fighting for his life, and finally dying.

Before the Norman Mailer Conference, I had participated in psychoanalytic conferences and written papers that were published in journals. Thinking about my life and setting it down on paper was a new experience. I dug into my memories, waited for my unconscious to work through the gray areas, and a piece of my life with Dad appeared. The writing flowed, and I enjoyed it. I thought I want to do more of this. And I also thought, many books have been written about Dad, but few people know what he was like as a father. I decided to plunge into unknown territory and began writing the memoir.

To lead off, a few facts: the three journalists Todd worked with are Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein and Ben Bradlee, the trio responsible for bringing down Richard Nixon by revealing his complicity in the Watergate break-in cover up. The first lady was Hillary Clinton.

Danielle Mailer enlisted local volunteers to help create a mural-like work, with enormous fish covered in bright patterns, along the Naugatuck.

The ideal biographical journey, as Vidal saw it, would skirt his social snobbery and namedropping; minimize his alcoholism; rationalize his sexual tourism in Bangkok.” Mike reviews Parini’s new biography of Gore Vidal in the TLS.

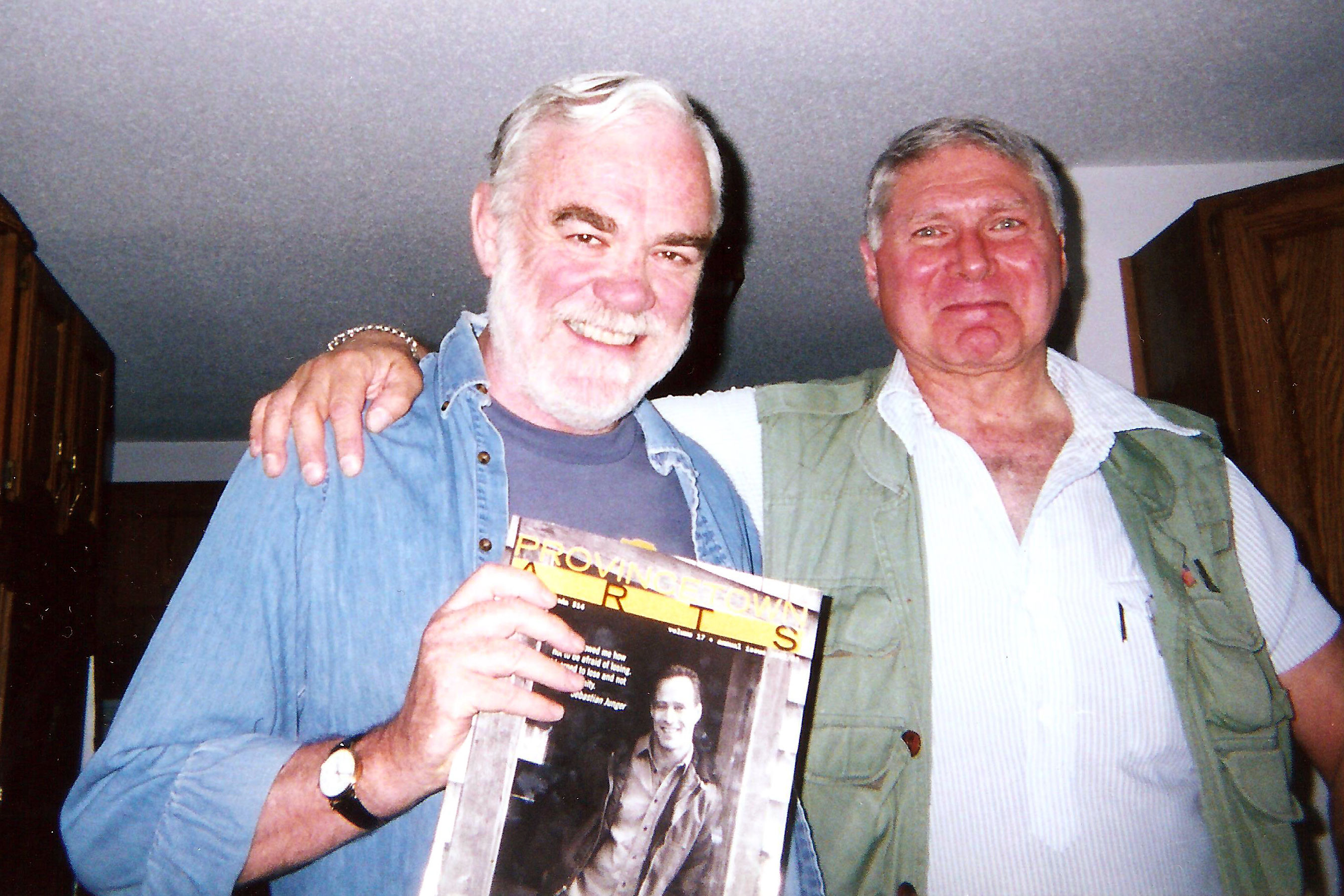

The latest issue of The Mailer Review reflects the celebrated author’s multifaceted personality with articles on some of his major works and reminiscences from his family.