Ali: A Life, by Jonathan Eig (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) $30.

Times Literary Supplement (November 24, 2017)

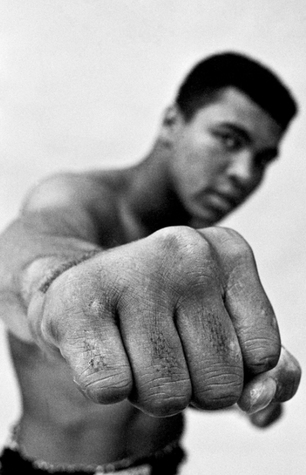

What clearly distinguishes Ali: A Life from the score of biographies preceding it – including even the best of them: Thomas Hauser’s Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (1992), David Remnick’s King of the World and the Rise of an American Hero (1998), and Gerald Early’s Muhammad Ali Reader (2013 – is the analysis of the number and kind of punches Ali gave and received, round by round, over the long arc of his career. Jonathan Eig enlisted CompuBox, Inc to anatomize Ali’s bouts, using film and video recordings. The analysis determined that after his first ten years of boxing, he took almost twice as many punches as he received. Furthermore, a plurality of Ali’s punches were jabs—he probably had the greatest left jab of all time—which while effective at discombobulating opponents, are not as destructive of brain tissue as hooks and uppercuts. The famous rope-a-dope tactic that Ali used to take the championship from Forman may have enabled him to win the fight, but the damage Foreman inflicted was terrible. In his last fight with Joe Frazier, the 1975 “Thriller in Manila”, Ali said that the pounding he received from Frazier (“the human equivalent of a war machine”, as Norman Mailer described him), “was like death, closest thing to dyin’ that I know of”. Eig deploys the CompuBox statistics sparingly, deftly, tellingly to demonstrate that a significant part of Ali’s unprecedented achievement as a fighter came from his willingness to take much more punishment than he gave out. He defeated Frazier in Manila to retain his title, but urinated blood for weeks. Sitting in his hotel room after the fight, he turned to a reporter, and said, “Why I do this”? Eig’s biography comes as close as we are likely to get to the answer.

Eig’s is the first biography of Muhammad Ali since his death in June 2016. He quotes James Baldwin to illuminate the teenage boxer’s decision to become the greatest fighter of all time. To survive in a racist society, Baldwin wrote, “one needed a handle, a lever, a means of inspiring fear” in the minds of oppressors. “Neither civilized reason nor Christian love would cause any of those people to treat you as they presumably wanted to be treated, only the fear of your power to retaliate” would accomplish that. At the age of thirteen, Cassius Clay adopted a Spartan regimen to become bigger, stronger, faster: no soda pop, alcohol or cigarettes; lots of milk, raw eggs and garlic water (to lower blood pressure). Run everywhere, train hard every day, go to bed early. His first trainer, Joe Martin, a white policeman in Louisville who worked with young boxers, said he was “easily the hardest worker of any kid I ever taught”. His training routine left little time for school work. He could barely read, and was mystified by mathematics. One of his classmates said that he was “dumb as a box of rocks”. His hero was Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion. “I grew to love the Jack Johnson image”, he would say. “I wanted to be rough, tough, arrogant, the nigger white folks didn’t like.”

Ali: A Life is scrupulously attentive to how deeply and how long Cassius Clay – and after his 1964 conversion to Islam, Muhammad Ali – was despised by both whites and blacks during the early stages of his twenty-one-year professional career. He was celebrated for winning a gold medal for the US at the 1960 Olympics for the US, but soon fell out of favour. A combination of braggadocio (the media called him “Gaseous Cassius”) and flirtation with the Nation of Islam, made him the maligned underdog when he fought Sonny Liston for the championship. Malcolm X (a key figure in Eig’s biography) encouraged Clay to see the fight as a battle between Christianity and Islam: “It’s the Cross and the Crescent fighting in a prize ring”. Ali later became adept at turning prizefights into symbolic encounters that burnished his image, but not in his victory over Liston, who was the fans’ favourite. He went on to defeat Liston again, and then agreed to fight the mild-mannered former champion, Floyd Patterson. In the run-up to the match, Ali called Patterson “the Rabbit”, and showed up at his training camp with a bag of carrots. Patterson was revered even by those who had no interest in boxing. Ali also called him an Uncle Tom, a name he smeared on many of his opponents.

By the time of the fight, November 1965, Ali had moved into the orbit of Elijah Muhammad, known as “the Messenger”, the leader of the Nation of Islam. He prophesized the destruction of “blue-eyed devils” by a hovering “Mother Plane” controlled telepathically by black pilots – the details of the annihilation remain occluded. While the Messenger had a large following, civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, as well as a majority of black and white Christians, were scornful of his bizarre separatist dogmas. But as Eig points out, “The Nation had given [Ali] discipline and focus . . . a sense of purpose and community”. Gene Kilroy, one of Ali’s friends, added, “If it wasn’t for the Nation of Islam, he could have been cleaning bus stations in Louisville”. The Nation also gave him a premonition of his destiny. Before defeating Patterson, Ali said he felt he’d been born to “fulfill biblical prophecies. I just feel I may be part of something – divine things”. It was his custom to thank Elijah Muhammad and Allah after his fights. Even after The Messenger’s death in 1975, Ali continued to praise him, though with noticeably less ardour as his own fame grew.

In the fourteen months between his defeat of Patterson and March 1967, Ali defended his title seven times, a punishing series even for a superbly conditioned athlete in his mid-twenties. Eig describes him at the peak of his powers:

Ali…boxed beautifully, changing speed and direction like a kite, cracking jabs, digging hooks to the ribs, sliding away in a shuffle to survey the damage, and then cracking more jabs, moving in and out with no steady rhythm, no pattern. He was a revolutionary, like Charlie Parker, with an innate style and virtuosity no one would ever reproduce. He turned violence into craft like no heavyweight before or since.

Ali was now “the most widely recognized athlete on earth”, Eig states, and also probably the wealthiest. A few months later, however, after refusing to be inducted into the US Army, he became the most hated. Stripped of his crown, he did not fight again for three-and-a-half years. With the encouragement of Martin Luther King, he became involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement, which he, like King, saw as inseparable from the civil rights movement. In one interview he said, “I don’t have no personal quarrel with those Viet Congs”. Another statement—dubiously but permanently attributed to him—became one of the mantras of the movement: “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger”. Staunch in his refusal to compromise with the government, Ali was broke, scorned, unemployed, and convicted of draft evasion.

His situation began to improve after the October 1967 protest march on the Pentagon, and the January 1968 Tet Offensive launched by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces. Anti-war marches grew in number, and protest grew into resistance. Ali’s actions and words were rallying cries. After a long legal struggle, his reputation was restored in January 1971 when the US Supreme Court unanimously reversed his conviction. By then, however, he was now in his thirtieth year, out of shape, and just one of a dozen boxers who had championship ambitions. It took seventeen fights over nearly four years for him to earn the right to challenge and defeat George Foreman, who had been champion for almost three years. Their epic 1974 match in Zaire, the “Rumble in the Jungle,” is arguably the best-known boxing match in history, in no small part because of the 1996 documentary, When We Were Kings. Eig makes no comment on the film, the only significant omission in this deeply researched, comprehensive biography. His prose is fast-paced, uncluttered, and rich in personal insights from the 600-plus interviews he conducted in the years just before and after Ali’s death. Eig managed to get the recollections of most of Ali’s entourage, including his doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, and the impresario and hustler, Don King (“Cash is King and King is cash”), many of his opponents, his brother Rudy and his four wives. The assistance of the last, Lonnie, who was married to Ali for twenty years, was extensive. He also received assistance from others who had written about Ali. Eig had both the advantage and the obligation to tell the story of Ali’s slow retreat into silence, a result of Parkinson’s disease.