By James Marcus

Times Literary Supplement, February 17, 2023

“Did you ever get in the boxing ring with Norman Mailer?”, a friend once asked me. The question initially struck me as an absurdity. He might as well have asked if I had shot skeet with Schopenhauer or played Twister with Toni Morrison. But it wasn’t absurd at all: the middle-aged Mailer, who worked out with a couple of trainers and wrote at great length about the sport, had a habit of sparring with his youthful admirers, and my friend, a few years older than me, was among them. I asked him what the experience had been like. “Well, I never hit him in the head”, he told me. “I didn’t want to wipe out any of Mailer’s brain cells.”

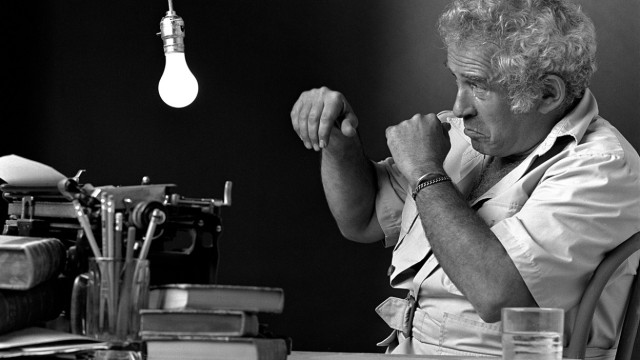

Mailer, born a century ago on January 31, 1923, always regarded boxing as a metaphor for art. Like his hero Ernest Hemingway, he treated writing and fighting as interchangeable agonies, with clear winners and losers. “People who write books take as much punishment as prizefighters”, he insisted on television in 1971, “and one of them has to be the champion.” To his fellow guests, including Gore Vidal, whom he’d head-butted in the green room before the show, he added: “I’m going to be the champ until one of you knocks me off”.

Was this bracing or idiotic? It was sometimes hard to tell. Mailer’s pugilistic itch was inseparable from his artistic ambition – which led to more than forty books, multiple bestsellers and a role in American culture unimaginable for any writer today. For decades it mattered what Mailer thought about Vietnam, JFK, Hollywood, race or feminism. He was the nation’s wild-eyed diagnostician; even his nuttiest ideas helped set the terms of debate. Yet his zest for combat was inseparable from a kind of religion of masculine bluster, which in Mailer’s case was sometimes merely rhetorical, but tended to erupt into physical violence.

He has not been cancelled. Much of his enormous output remains in print, and a work such as The Executioner’s Song, which won him the Pulitzer prize in 1980, continues to shift 1,000 or so copies every year. Still, his star has dimmed. Penguin Random House, which had been contemplating a new anthology of Mailer’s nonfiction to mark his centenary, scuttled the project last year. The reasons were a little vague. Either Mailer’s 1957 essay “The White Negro”, with its hipster poppycock and patronizing view of Black Americans, was now too much for contemporary readers to swallow, or the anticipated financial returns were too meagre.

Which is not to say his centenary will pass unmarked. At least four books have been issued in recent months, all of them meant to celebrate Mailer’s life and art, which were joined at the hip. Let’s start with Richard Bradford’s Tough Guy. Bradford, who has published more than thirty books, including warts-and-all portraits of Patricia Highsmith and Hemingway, likes to engage with turbulent personalities. With Mailer, he has hit the jackpot. It was Vidal, in an affectionate 1960 essay, who suggested that his old friend had a “nice but small gift for self-destruction”. That was an understatement. Mailer’s gift for self-destruction was vast, iridescent, iceberg-sized, and Bradford spends much of his book trawling through the wreckage. His priorities are clear from the first pages: a brief catalogue of Mailer’s follies and the resulting havoc, with the promise of more, all of it “beyond reason, inexplicable … grotesque and addictive”.

The carnival-barking tone is muted in the initial chapters, during which Mailer is too young to make a mess of anything. On the contrary, this Brooklyn Jew with an adoring mother and a slightly disreputable father (gambling problem) is depicted as a brainy weakling. There is, however, a taste of things to come when Mailer goads the audience at his bar mitzvah by declaring his allegiance to Karl Marx. This bit of adolescent chutzpah charmed me, like something out of a Mordecai Richler novel – Duddy Kravitz as a red diaper baby. Bradford sees a dark premonition, the pimply provocateur already “choosing to bludgeon the truth into what he thought suitable for the occasion, usually involving an attempt to shock”.

In any case, the precocious Mailer, just sixteen, was packed off to Harvard in 1939. There he shifted his focus from aeronautical engineering to English literature and met the first of his six wives, Bea Silverman, who drastically sped up his erotic, cultural and political education. There was, of course, a further accelerant: the entrance of the US into the Second World War at the end of 1941. Mailer knew he would be drafted the moment he graduated, but, as a fledgling writer, he already had his eye on the main chance. As he later recalled, “I was worrying darkly whether it would be more likely that a great war novel would be written about Europe or the Pacific”. Mailer, who served in the Pacific theatre as a file clerk, reconnaissance rifleman and mess cook, settled the question himself with The Naked and the Dead (1948).

The book brought its twenty-five-year-old author instant fame and fortune. How does it hold up? The Naked and the Dead has now been reissued by the Library of America in a handsome edition that includes a generous selection of the letters Mailer sent to Bea and various other relatives during his military service. These were notes for the novel he already knew he was writing the minute he set foot on the Philippine island of Luzon, where he spent most of the war. They were his seed corn, his skeletal material, sometimes quoted almost verbatim.

Yet the novel never feels like a scarecrow production, patched together from blurry V-mails to the author’s wife. It is a big, vivid, grimy, incessantly curious narrative, punctuated with scenes of combat, but much more focused on the quotidian misery of men at war, whose frequently boring and bureaucratic tasks take on a strange heroism by virtue of their proximity to death. It is also, as Bradford points out, “a book about America, a nation whose tribalist, class-based and psychosexual tensions are crystallised in US servicemen sent somewhere else, somewhere particularly alien”.

The Naked and the Dead is a young man’s book – one Mailer himself later referred to as “the work of an amateur”. It is flawed. Following the classic formula, the soldiers represent a schematic cross-section of American life, and you can almost see Mailer checking off the boxes: rich and poor, Jew and Gentile, loafer and libertine. His excursions into the childhoods of his characters are particularly creaky. Still, the novel remains a marvel of postwar naturalism, with plenty of room for Mailer to dive beneath the hardscrabble surface. When he writes of one character feeling “a sense of mystery and discovery as if he had found unseen gulfs and bridges in all the familiar drab terrain of his life”, the elation is Mailer’s, and ours too.

Success was sweet, and success was crushing. Mailer’s sophomore slump, which lasted for the next seven years, yielded two novels, both critical disasters: Barbary Shore (1951) and The Deer Park (1955). As his first marriage collapsed he flirted once more with Marxism, tried his hand at screenwriting and dosed himself with booze, weed and Seconal. He wrote a series of increasingly unhinged columns for the Village Voice, which he had helped to found in 1955. He ran for mayor of New York City. It was no longer clear whether Mailer was a novelist, a social theorist, a politician, a hedonist or a hack. His identity was up for grabs, he later wrote, as fame and mass media transformed him into a “node in a new electronic landscape of celebrity, personality and status”.

He only began to grope his way out of the wilderness with Advertisements for Myself (1959), which struck many contemporaries as a holding action. Yet this nonfiction miscellany was something new: an omnium-gatherum of the self, or selves, since Mailer had finally embraced his fractured nature and decided to wave all of his multiple personalities inside the tent.

It also pointed the way to the nonfiction triumphs of the late 1960s, especially The Armies of the Night (1968). Here Mailer introduced himself as a fully-fledged character – the hero, so to speak, of the famous, celebrity-studded March on the Pentagon in 1967. His third-person presence in the narrative produced a split-screen effect, alternately inflating and mocking the action figure known as Norman Mailer. “The architecture of his personality bore resemblance to some provincial cathedral which warring orders of the church might have designed separately over several centuries”, he wrote. Whether lampooning his fellow protesters or being loaded into the paddy wagon by National Guard troops, Mailer turned the tumult into a stinging (and often hilarious) cultural critique. In one fell swoop he also aligned himself with the New Journalists and anticipated by decades the hybridized shenanigans of latter-day autofiction. Not bad for a single book, which won a Pulitzer prize and the National Book Award, and provided Mailer with the blueprint for much of what he wrote throughout the 1970s.

Many writers would have stopped there. Twenty years in the spotlight, a few trophies for the mantelpiece, a blissful retirement. Not Mailer: his madcap progress continued until his death in 2007. There were more books, more wives, more children, more real estate, more polemics. There were also more physical altercations. Some, like his ear-biting tussle in the grass with the actor Rip Torn, are preserved on film. The most momentous, of course, had taken place in 1960, and represented the nadir of Mailer’s existence: the stabbing of his second wife, Adele Morales, during the drunken launch of his first mayoral campaign.

There is no excusing or minimizing this atrocious act, which led to a suspended sentence for felonious assault and landed Mailer in the psych ward at Bellevue for seventeen days. Morales, who survived the attack, made an attempt to reconcile with Mailer, but divorced him in 1962. By then, however, his brief period as a social pariah had ended and he was allowed to resume his place in the cultural landscape.

The willingness of Mailer’s peers to forgive (or at least tolerate) this assault seems old-fashioned in the worst sense. Yet it’s also true that he elicited this response more generally, even from people inclined to view him with extreme scepticism. Elizabeth Hardwick, for example, noted the “large proportions of Mailer himself, his confidence and intrepidity, his florid pattern of experience, his disasters met with an almost erotic energy of adaptation”. There was an affection, even a kind of tenderness, for his intermittent lunacy – as if the proprietors of the china shop were ultimately charmed by the bull.

That is certainly the flavour of Mailer’s Last Days, a collection of essays, reviews and reminiscences assembled by J. Michael Lennon. The author is a key member of Mailer’s inner circle, whose CV includes the massive Norman Mailer: A double life (2013), as well as several other related books. He is also Mailer’s “bibliographer, editor, flunky, friend, biographer, and eulogist”, not to mention his official archivist. His personal collection of items includes not only Mailer’s dental records, but also his false teeth.

Lennon can be quite blunt about Mailer’s failings as a novelist. “His plots are a disaster”, he concedes to one interviewer. “He could never figure out how to do them.” He also confirms the instincts of this reader, and others, that Mailer’s books are often bloated – that he was too enthralled by his own Melvillean fluency and didn’t know when to stop. Yet Lennon’s affection for the older man, who clearly functioned as a surrogate father, suffuses the entire collection and is especially evident in the diary entries that track the final two years of Mailer’s life. The angle is intimate, the details often touching. In the twilight Mailer is an appealing figure, whether he’s kibitzing at a poker game or planning his next novel (about that crowd-pleasing duo Rasputin and Himmler).

Like Lennon, the novelist and critic Robert J. Begiebing is an insider: a founding board member of the Norman Mailer Society who has written two previous studies of his idol. His book, like Lennon’s, is a miscellany, including essays, a dramatic dialogue and two interviews (one real, one imaginary). This is not necessarily a recipe for coherence. Indeed, I suspect both men had Advertisements for Myself in mind when compiling their tributes, hoping that the disparate materials would attain some kind of fusion. Lennon did himself no favours by inserting a series of unrelated (if excellent) reviews into the midsection of his book. Begiebing has made no such mistake in Norman Mailer at 100: he keeps his focus firmly on the matter at hand.

His method, for the first ninety or so pages, is to pair Mailer with a sequence of exemplary figures: Hemingway, Carl Jung, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Joan Didion and so on. These juxtapositions yield some fascinating material. Who knew, for example, that Didion considered Mailer “one of the few people who can write about sex without embarrassing me”, or that Mailer’s massive journal of the mid-1950s, mostly composed while he was stoned out of his gourd, owed so much to Jungian principles? The essays are scholarly in tone, even a little diffident, which seems like a mismatch – doesn’t Mailer dictate a more bare-knuckles approach? But perhaps Begiebing is onto something. When he interviewed Mailer in 1983, this most aggressive of writers suggested that he might be a passive vessel after all: “If there’s anything up there or out there or down there that is looking for an agent to express its notion of things, then, of course, why wouldn’t they visit us in our sleep? Why wouldn’t we serve as a transmission belt?”

Mailer taking dictation from the divine is a funny thought. No doubt he would have considered it a conversation between equals. But before we get too carried away with this picture of him as a recording angel, a gentle intermediary between eternity and the reader, we should bear in mind a detail from J. Michael Lennon’s deathbed chronicle. Mailer was buried in his boxing regalia – a fighter to the end.