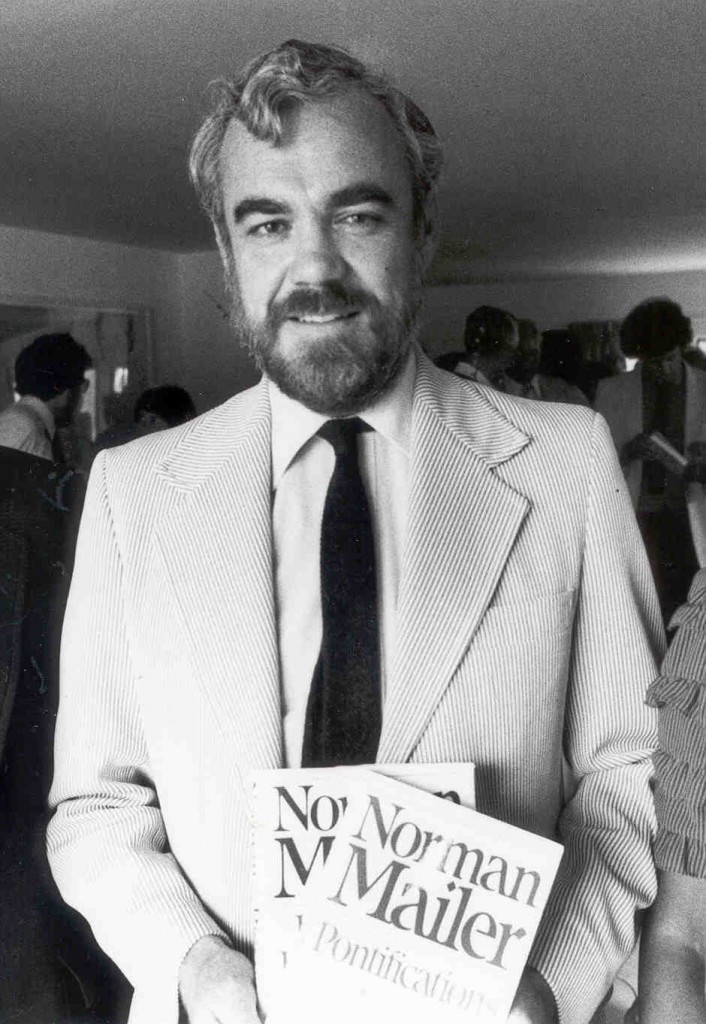

I was sorting through some papers in preparation to pick up work on the edition of Mailer’s letters I am editing for Random House. I found a sheet of paper containing the citation accompanying the JJLS Lifetime Achievement Award given him at the Society’s meeting in Paris, June 22, 2002. It was a terrific conference, and Mailer, his wife Norris and George Plimpton did a reading of the letters of Hemingway, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald at the American Church on Quai d’Orsay.

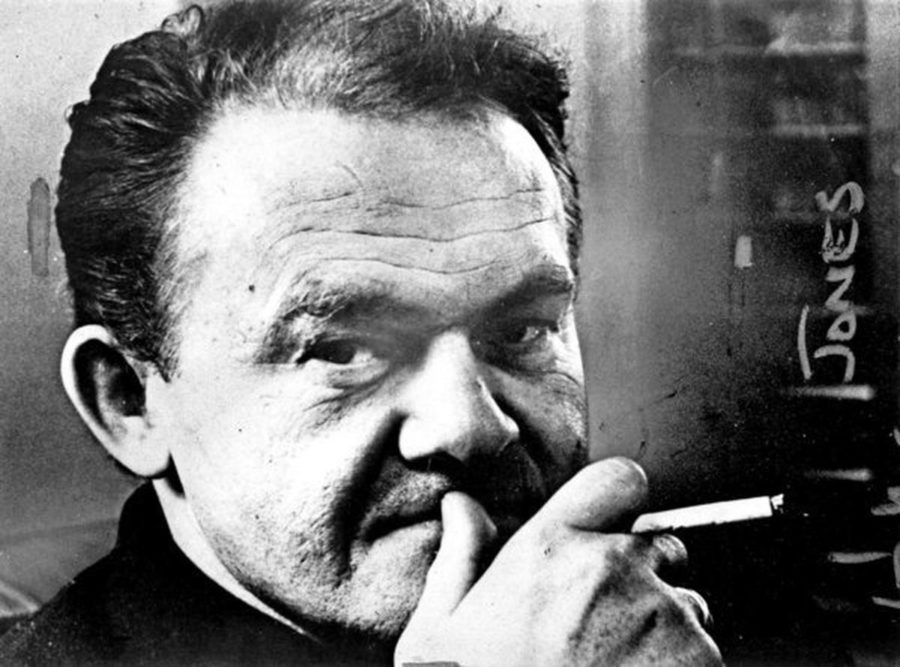

Scribbled on the paper were some of the things Mailer said about Jones when he spoke on a conference panel. He said, “Jones took beautiful swings at the bastards,” meaning no particular individuals, but the whole gamut of assholes and shits in contemporary society. He went on to say that in his writing he was fearless, and “pressed wounds to the other side.” Jones, he continued, “had his finger on the nation’s pulse for 40 years.” He ended his remarks with this: “Jones disabled the grief button by embracing life like no one ever has.”

These fragmentary notes made me recall a letter Mailer wrote to William Styron in July 1953, shortly after Mailer visited the Handy Writers Colony, and which I quote from in my forthcoming biography, Norman Mailer: A Double Life. Jones’ gusto always fascinated Mailer. Here is an excerpt from the letter:

Lowney Handy and Jones are people whom one can satirize so easily, and yet one’s missed it all, for both of them are such extraordinarily passionate people, that their errors as well as their successes have a kind of grotesque to them. Lowney Handy burns—I kept thinking of fanatics like John Brown when I looked into her eyes. Jones like all of us is having his troubles with the second book, but everything happens to Jonesie on so big a scale that his troubles are flamboyant next to ours, and involve money, movie scripts, gymnastics, obscenities, raw insecurity, triumphant phallicism and wham, wham, wham, it’s all explosion. With it all, I like him tremendously. I suppose I have the kind of friendship with him that I had when I was a kid with other kids.

From James Jones Journal (19.1) Spring 2013.