Reprinted from Ocean State Review, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2016)

Note: The following is the first chapter of a work-in-progress, “Sixteen Handshakes to Shakespeare: From Bishop to the Bard.” Proceeding backwards in time, it will consist of accounts of sixteen meetings over four centuries between literary figures, English and American, famous and obscure, all sharing an intense interest in the work and life of Shakespeare. The first chapter is devoted to Elizabeth Bishop and Ezra Pound.

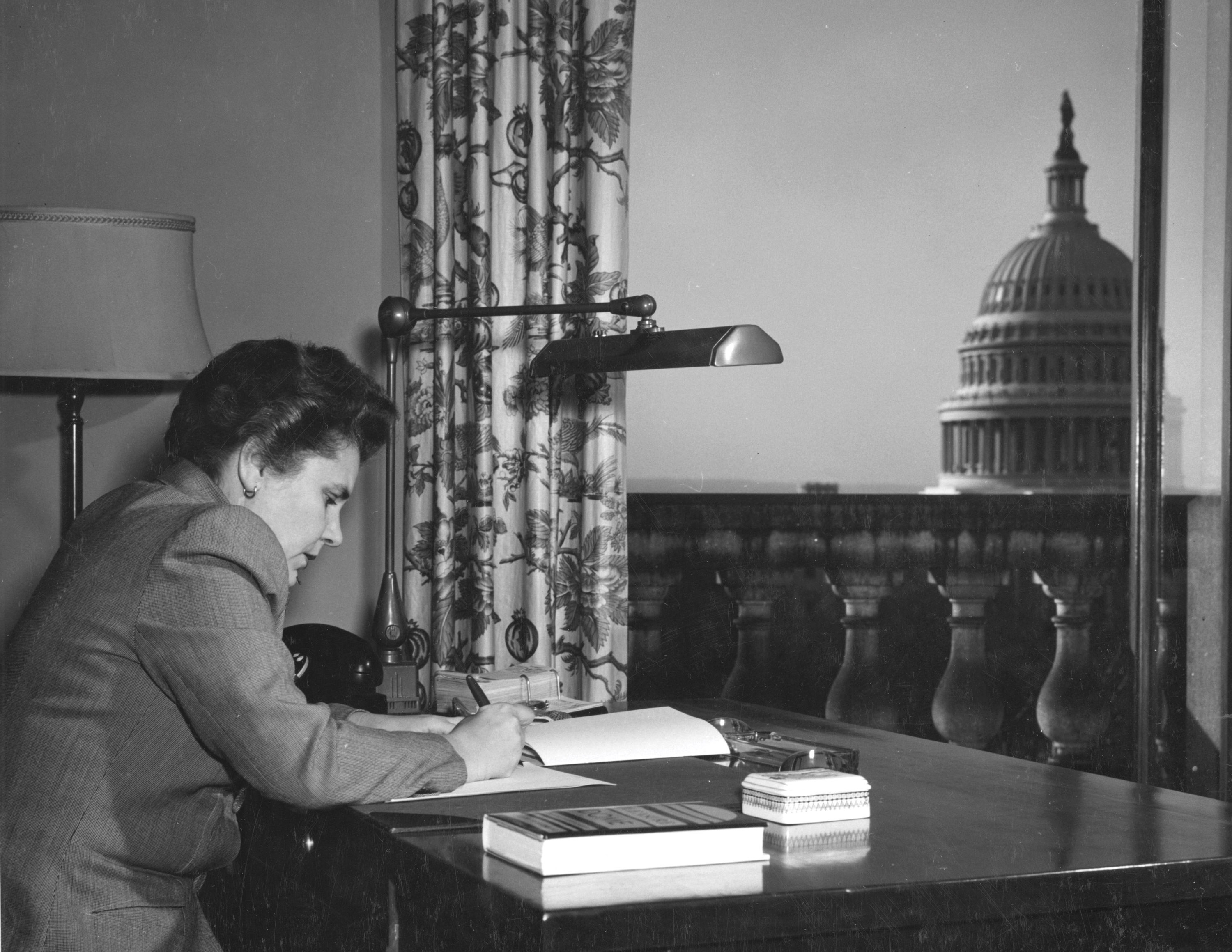

When Elizabeth Bishop visited Robert Lowell in early May of 1948, he took her to see Ezra Pound, who had been incarcerated since late 1945 in St. Elizabeths Hospital, a government psychiatric facility in Washington, D.C. Lowell, then 31, was the most important and ambitious young poet in the country, having won the Pulitzer for poetry in 1946—edging out Bishop’s first book, North & South—and named the following year as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress (a title later changed to poet laureate). Bishop, 37, unmarried, unstable and still uncertain of her sexuality, had met Lowell a year earlier, and was smitten by this tall, rumpled Yankee who she found to be handsome in “an almost old-fashioned poetic way.” He was the first person she had ever met who really spoke with her about how to write poetry—“like exchanging recipes for making a cake,” as she put it. For the next thirty years they enjoyed a warm and complex, but not intimate, relationship.

As poet laureate, Lowell had an unofficial responsibility to visit Pound in the “bughouse,” as the elder poet called it. Both he and Bishop were in awe of Pound, the brilliant editor who had acted as midwife to The Waste Land, the masterpiece of his friend T. S. Eliot, who dedicated the poem to Pound as il miglior fabbro (the better craftsman). Pound had long been an innovative and generous supporter of many writers—William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, Hilda Doolittle, Ernest Hemingway, William Carlos Williams, and Marianne Moore, to name the most prominent—but he was also tendentiously opinionated and surpassingly narcissistic, and perhaps worse, at least in the opinion of a quartet of psychiatrists from St. Elizabeths, led by its superintendent, Dr. Winfred Overholser. They examined him to see if he was sufficiently sane to be tried for making treasonous, anti-Semitic broadcasts, over 300 of them from 1941-45, against the Allies on Italian government radio in Rome. In early 1946 Pound was declared by a federal court to be “a sensitive, eccentric, cynical person” now in “a paranoiac state of psychotic proportions which renders him unfit for trial,” and ordered confined to the derelict ward at St. Elizabeths.